He highlights the significant challenges including Scotland's public health record, our changing demography and the economic environment. Over the next 10 years the number of over 75s in Scotland's population - who tend to be the highest users of NHS services - will increase by over 25 per cent. By 2033 the number of people over 75 is likely to have increased by almost 60 per cent. There will be a continuing shift in the pattern of disease towards long term conditions, particularly with growing numbers of older people with multiple conditions and complex needs such as dementia.

You can read all the achievements in the report but the highlights are lower waiting times, greater efficiency savings, reduction in hospital infection and reductions in deaths from cancer, stroke and heart disease. Healthcare in Scotland is also safer with the most recent Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio (HSMR) statistics, showing a reduction of 10.6 per cent since December 2007. Patients are also generally happy with the treatment they receive with satisfaction ratings of around 90%.

The report also claims longer term progress:

"One of the most significant achievements is the fall in premature mortality in the past 20 years, which has decreased by over a third. This includes a 2 per cent decrease in the latest year alone. Premature mortality, a key indicator of the health of Scotland's population, measures the death rates of those aged under 75. In 1991, there were 540 deaths for every 100,000 people aged under 75. By 2011, the figure had fallen to 349."

Chart 1

What this doesn't say is that Scotland's relative position hasn't changed much, as the Sick Man of Europe report shows.

There are lots of numbers reflecting health promotion activity covering alcohol, smoking, drugs and physical activity. Somewhat lighter when explaining how all this is reducing health inequality.

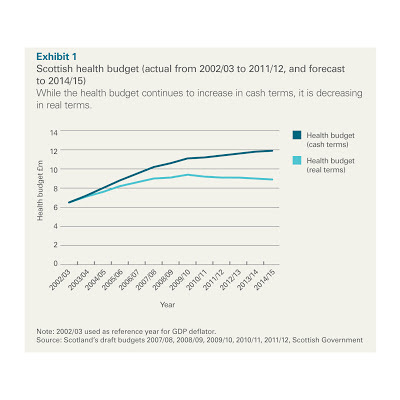

The financial chapters paint a somewhat more rosy picture than the more objective Audit Scotland report. This chart shows how the £10,537 million is spent.

Chart 16

For the financial year 2011/12, NHS Boards delivered local Efficient Government savings of £313 million, representing 3.6 per cent of baseline funding against the 3 per cent efficiency target. So there is the cash to solve the pensions dispute?

While this is a glossy spin with the warts left out, it does none the less indicate that NHS Scotland and more importantly its staff, is generally performing well and delivering on the key targets. Solutions to Scotland's longer term health inequalities remain more challenging and needs more than NHS delivery..